We’ve all heard of particular singers who do or don’t write their own songs, so it’s not unusual to us for us to find out the singer or frontman we’ve connected with is just the singer and it’s actually the guitarist, or bass-player, or drummer, (who is also often the back-up singer) who is the one behind all those songs we connected with. It’s an interesting phenomenon because we often feel this subtle mixed bag emotions; first, a slight sense of betrayal towards the singer for misleading us and pretending they were his own songs, secondly, a greater warmth, perspective and empathy for the actual songwriter in the band, thirdly, a new sense of understanding about the actual working dynamic between the band members and fourthly, a small sense of nostalgia for simpler times, when, like a child, you could believe that everyone was who they seemed to be at face value.

But we shouldn’t be so surprised, really. Even before reality television began churning out singers for our admiration and amusement in shows like Idol and X-Factor, record companies have built the careers of singers that have proven capable of making them money.

In fact, if you take it back further past the all pop stars and girl groups and boy bands and Jacksons and Osmonds and more respectable rock bands that wrote their own songs and Elvis and Roy Orbison, right past the beginnings of the modern singer-songwriter to the beginnings of the 20th century and older, you’ll hit a time when basically everybody sang as part of daily life. It was a common pastime that everybody did at home, at church, while they worked in the field or around the house, in the evenings with your family as a chief form of entertainment, and at other social gatherings. Most people developed reasonably good voices over the years, but it wasn’t much more than a fun way to pass the time and connect with other people.

Conversely, professional singers were the rare, exceptional talents, spotted at an early age, often in the families of established musicians, who were trained vocationally from the time they could speak to sing and sing brilliantly. And the masses would go to hear them sing, because everyone had a personal connection to singing, but didn’t really consider it more than entertainment. It’s quite interesting; we tend to think of ourselves as more advanced than they were 200, 300, 400 years ago, etc., but there was also a level of single-minded devotion to one life-long career path that has all but disappeared nowadays.

(I’m not rambling, honestly. I’m painting a verbal picture for you, just wait for it.)

Nowadays, most of get us between 12 and 18 years of relatively broad schooling (at least half of which we’ve forgotten by adulthood), learning about the world around us and everything in it from the “safe” confines of an overpopulated classroom. In fact, we probably won’t get our first hints of genuine vocational training until our late teens/early twenties, at which point we’ll probably work a 40-hour (out of a possible 168 hours) work week, 40-48 (out of 52) weeks of the year. This means that the average person will gain 1600-1960 hours (less than 2,000 hours) of work experience year in their chosen profession. In short, it will take the average adult 5 to 7 years of experience in their position/career to become a 10,000-hour “expert”.

A few hundred years ago, a professional singer would have had more experience than this several times over before their voice was even considered mature enough to perform any solo pieces on stage, in church, or for the nobility. Your average professional singer in their twenties would have had the experience level of Andrea Bocelli, and they would likely live and continue performing for another 30 to 40 years, maturing their voice as they went.

There was a level of wholehearted devotion to your vocation back then that we see much less of nowadays, and that had a significant effect on the musical outcomes. While all composers could undoubtedly sing to some degree (as they were expected to have some working knowledge of every instrument), singer and composer were usually very different roles filled by very different people. They often clashed professionally and privately, with a lot of composers marrying professional sopranos, and much has been made by historians about the degrees to which a diva wife may have helped or hindered her husband’s compositions thereafter. And we still see these roles play out similarly today.

The point in all this, from a professional, music-industry standpoint, is that you almost never have high-calibre singers (even today) who are also high calibre composers. You tend to get great singers with little to no songwriting ability, or merely decent singers who are great songwriter-composers. Rarely both. And I think it all comes back to their instrument. The voice is part of your body.

While a significant portion of instrumentalists read music and understand music theory, singers more than any other instrument tend not to bother, relying instead upon their ears. Because, of course, it’s not an instrument, it’s their own body. They don’t need an instruction manual. Just a bit of practical know-how, practice and training. And they certainly don’t need a working understanding of musical theory to be able to replicate the sounds they want with their voice. So, most singers don’t bother.

The fundamental problem with all this is, however, that as the frontman, the lead performer, the one to whom the audience look to for connection, they have a fundamental desire to be able to express themselves through song. More than any other regular instrumentalist in the band, the singer tends to want to write their own songs the most, but is also often the least qualified to do so.

One of the biggest developments in the entertainment industry over the past 70-80 years has been the development of fandom, the relationship between an entertainer or creator and their fans. Our prominent means of viewing entertainment has shifted from domum exterius to domum interius; in our homes on screens and phones and tablets, making television, radio, and now internet/YouTube stars, in particular, seem to us like our best friends; authentic, interesting, loved, welcome in our private spaces.

This has in turn created a natural demand for authenticity from our stars. Statistics show that movie stars are most removed from this effect. But singers… Music is intensely personal to most people. Regular people feel a connection with their favorite singers, and more and more, the singers, in turn, feel a tremendous obligation to their fans to be authentic with them. So we have this effect where, particularly in the last 10 years, high-calibre singers with large fanbases, who would never have written their own songs in the 90s, feel a much bigger obligation to write/co-write their own music or, at the very least, lyrics.

Because of this, we fully expect one of the biggest demographics for Sound Songwriting to be, in fact: singers, wanting clear tips, tools and techniques for writing their own songs, particularly because it’s becoming more and more expected of them by their fans. As such, it seemed vital to address this blindspot in an article on melody writing, elucidating some of the things you might have learned if you’d been formally trained in music theory.

What is the melody and how does it work?

The melody is a single musical line that features over an underlying or implied harmonic structure. In terms of songwriting, which is the context/framework we’ll be operating within for the remainder of the article, the melody is the pitch and rhythm pattern attributed to lyrics and sung by the lead singer(s), plus any noteworthy instrumental riff and/or solo not played underneath the main melody.

A melody is comprised of 2 different varieties of notes: arpeggio notes and embellishment (or embellishing) notes, all of which should occur diatonically; within the scale/key of the song (unless, of course, the key center has shifted). A particular key or scale will usually give you 7 notes to choose from in any octave you wish. 3 or 4 of these will be arpeggio notes, and 3 or 4 will be embellishment notes, though arpeggio notes will usually feature over 80% of the time. A good melody is predominantly arpeggio notes.

Arpeggio notes are chord notes. A particular chord will form an underlying harmony at any given point in the song. In example, the notes in the C-chord are C, E and G. In the key of C, without any key changes or non-diatonic chords, our potential melody notes are: C D E F G A B C. The C, E and G are the arpeggio notes over that particular chord. However, if my chord shifted to the dominant, the G7-chord, my new arpeggio notes are now G, B, D and F.

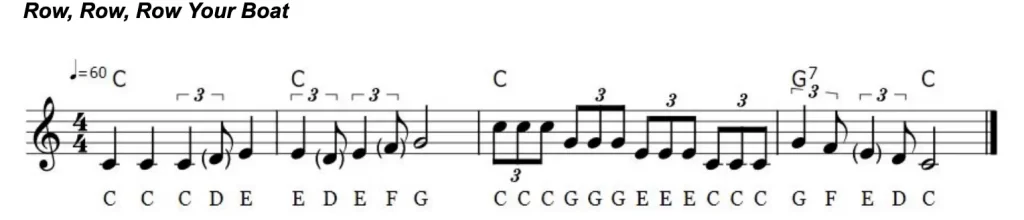

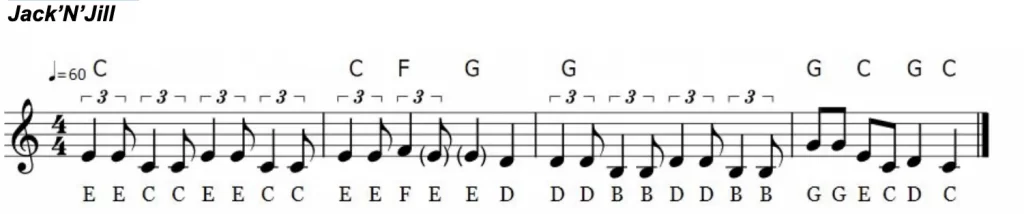

You can see this pretty clearly in Row, Row, Row Your Boat. The melody is predominantly C, E and G notes over the C-chord, and G, B, D and F notes over the G7-chord.

Embellishment notes (also called embellishment tones) are non-chord notes played over the chord. They tend to sound naturally unstable and, to our ears, want to resolve quickly to a chord note. This is why they tend to make up less than 20% of a melody. However, it is usually the interplay, conflict and tension-to-resolution that is created between the arpeggio and embellishment notes that makes a melody most interesting. There are several different types of embellishment notes. the names and rules of which vary slightly between countries and disciplines.

A Passing Tone is an embellishment note that works as a stepping stone connecting 2 adjacent arpeggio notes. 3 of the 4 embellishment notes above are passing notes (ie. the D in the 1st bar).

A Neighbor Tone is also an adjacent stepping stone, but instead of connecting 2 arpeggio notes, the neighbor note steps away and then steps back again to the same chord note. The D-note in the 2nd bar is a neighbor note to the E.

An Appoggiatura is an embellishment note where a stressed/accented beat falls on a non-arpeggio note then quickly resolves by step to an arpeggio note. The A-note in the first full bar does this, with the A resolving to the G-note in the C-chord.

An Escape Tone (the G-note in the third full bar) is like a neighbor note, but instead of resolving back to the same chord note (the A), or continuing in step like a passing note (to the F-note), it resolves with a wild leap in the opposite direction. If the underlying chord did not change mid-bar as it does, it would naturally leap up to a C or an F.

A Suspension is basically a form of appoggiatura in which the note preceding the non-chord tension note is the exact same note, thus appearing like a note from the preceding chord was suspended over the chord change, and resolved late. The F-note in Bar 3 and the first E-note in Bar 4 are both different types of suspension. The F-to-E suspension over the C-chord is called a 4-3 suspension because the 4th note from C resolves to the 3rd note from C. Following that same principle, the E-to-D suspension over the G-chord is therefore a 6-5 suspension. A suspension that resolves upwards is known as a retardation.

An Anticipation tone is a form of embellishment tone in which a note from the next chord change comes early to set it up more dramatically. In this case, we have an anticipation tone in Bar 2 directly setting up a 6-5 suspension to really draw out that tension before the resolution arrives.

There are some other lesser-used derivations on the above key embellishment tones, such as double passing tones, chromatic passing tones, double neighbor tones, etc. but they’re all just logical extensions of these core ideas above.

Perhaps, the biggest thing the above examples illustrate, however, is just how much melodies rely on arpeggio notes. I had to cycle through a fair few nursery rhymes to find these examples, and some of them, let me tell you, had zero embellishment notes whatsoever. It was just all arpeggio notes. Or all arpeggio notes and a passing tone in there once for good measure.

I said it once, I’ll say it again; good melodies are generally more than 80% arpeggio notes. And you’ll find that you tend to follow these patterns instinctively when building a melody by ear. One thing actually understanding what these notes do (and the names for them) does, though, is make you consider your options instead of just using the first thing that comes to mind. A little bit of key knowledge can be the answer to the effect or feeling you’re trying to create at any given moment.

Note Hierarchy

Now, I’m going to expand upon the dichotomy above (between arpeggio notes and embellishment notes) in a way that doesn’t get taught in the theory textbooks (because I developed it myself) but is just as discernible and instinctive by ear (to someone with standard Western music sensibilities) when you’re creating your own melodies at home.

As I began to learn about music theory in more detail, like arpeggios being the best melody notes and all the embellishment stuff above, I noticed a little number quirk that made me smile. I realised that you have your standard 7-note scale, then your 5-note pentatonic scales, and then your standard 3-note chords/arpeggios, and then it dawned on me that things in music seemed to prefer odd numbers over even numbers. When you’re building a chord, you start with 1, 3 and 5. Then, if you continue adding extensions, you generally keep going; 7, 9, 11, 13, etc. Even numbers don’t typically work as well. They tend to be suspensions and want to resolve back to odd numbers.

Well, I left it at that and thought nothing more of it for a long period of time. Later, however, as I began to take on guitar students and teach them about constructing good melodic guitar riffs and solos, how to build your melodies around these arpeggio notes, etc., I found myself reverting to pentatonic scales a lot, because they automatically remove the most dissonant notes from the scale, and your guitar solos automatically become 40% more melodic when you cut out the semitones.Shortly thereafter, I constructed something I call the Pyramid of Priority, sorting the notes in a key/scale into tiers based on their perceived value, strength and stability as melody notes.

Some notes just pull more weight for you than others, and knowing the hierarchy in play gives you greater control over the outcome. Shortly thereafter, I created the Minor Pyramid of Priority, for minor keys and chords, because the hierarchy plays out a little differently in terms of semitone placement.

But the more I played with these as a concept, the more I realised that the numbers within the individual tiers were still unevenly weighted. That 5 was more stable than 3, 6 more than 2, and 4 more than 7. So, in the end, I developed a single-note hierarchy for every chord in the key, from most stable to most dissonant.

I know, I know. It’s a bit crazy overboard, but, honestly, don’t worry. I wouldn’t expect you to have these memorized until you understand the finer workings of modal pentatonics, and unless you’re doing more advanced jazz or metal stuff, you really don’t need to worry about it ever.

The big important thing, though, is that I’ve done all the work here, and now you have access to it. You have a guidebook here of the most stable to the least stable notes for any given chord within the key. I’m not really going to get into percentages and advanced application techniques for this stuff, because I think just knowing that such a hierarchy exists and knowing where you can find it (should you need to) is going to be useful enough.

Obviously, you don’t want to always pick the most stable note for every chord all the time. That would be extremely exhausting. As we learned from our melody examples above, approximately 80% of the time we want something on the more stable end, and we also want some tension. A road that is dead straight for miles and miles loses our attention. We need some curves along the way to keep things interesting.

Also, generally, you want to move by steps and leaps. Usually more steps than leaps. If you only ever sang the root note for each chord, well, it would start to sound like a really boring bassline. Maybe you want root notes on key words, or at the beginnings and endings of phrases. And maybe words that are more painful or emotional vulnerable can naturally be more dissonant. This guide is a tool for you, so you can unpack your melody that’s just not quite working, and really get under the hood. With it, you can see where your problem is and some possible solutions.

And if you’re not sure about this sort of odd clinical approach, just go have a listen to Defying Gravity from Wicked or All I Ask of You from Phantom of the Opera. They both have an unusually high amount of large, seldom-used leaps to unexpected notes, and both were wildly popular in their times. But the notes work out in pattern with the chords. There’s tension when they want tension, and stability when they want stability.The more you dig into great melodies to see what makes them great, the more you’ll see these tools at play. Hopefully, you singers especially can really make use of the tools and rules, and stop asking yourself, where am I going wrong with this song? Why isn’t this melody working? How do I fix this broken repetition? Because now you have a way to figure it all out.

The Best Melodies to Take Inspiration From

What we want to do now is to take a quick look at some of the most popular music out there that is regarded for having some of the best melodies of all time. The following music creators are ones that you should absolutely be familiar with.

- Ray Charles’ Georgia on my Mind is often regarded as having one of the best melodies of all time. It is a very unique melody, yet is still very easy to sing along to and to remember. It’s extremely sultry and allows for plenty of improvisation, as jazz music should.

- Emily West’s I Hate You, I Love You Again is a very simple yet deep song that has the ability to touch people’s heart strings right from the first note. This is an extremely emotional breakup song, one that serves as perfect inspiration for your next relationship themed song.

- Queen’s Killer Queen features one of the most beloved melodies of all time, and it’s generally all thanks to the creative genius that is Freddy Mercury. As far as this genre of music is concerned, this is definitely a one of a kind song. This memorable melody is one that will go down as one of the best of the century.

- Jackson 5’s ABC is often considered to be one of these iconic songs with one of the best melodies of all time. Its simplicity is exactly what makes it so great. It also happens to have one of the best bass lines out there, something else that helps make it one of the most successful songs of all-time.

- Celine Dion’s My Heart Will Go On is often considered to be one of the most emotional melodies out there. It was of course written for Titanic, so you know that it’s going to be an emotional piece of music, especially with Celine Dion at the helm. This is one song where the benefits of melodies can definitely be seen.

- The Brothers Osborne’s Heart Shaped Locket is another all-time favorite as far as melodic and lyrical genius is concerned. These country music stars have really taken it to the next level, and it can be seen by the millions of music fans that connect so deeply with these artists. This is a song that you can truly connect with on an emotional level, and it’s all thanks to a melody that already tells a story by itself, without any lyrics needed, although they certainly help add to the equation.

- Paxton Ingram’s Break Every Chain took the world by storm when it was first performed on The Voice. It’s just a very deep, emotional, and inspirational song. As far as vocal music goes, this is one of the most inspirational of all time, especially as far as the current music scene is concerned.

- Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah is just a simply beautiful song with a melody that will melt your heart and lyrics that will make you cry a river. This is the kind of song that can be very deep on an emotional level, all without ever having to listen to any lyrics. It’s almost like the lyrics here are nothing more than a translation for the story that the melody itself tells so beautifully. As far as a melodic hook is concerned, this is one of the all-time best.